Becoming Time: Thinking and Feeling Time Through Audiovisual-Physical Media

My final project for the Audiovisual Cultures Masters at Goldsmiths was an extensive exploration of time. The result was a multimedia installation and a big fat practice research essay. I have documented the install as best as possible- below you can see a video of what was happening in the room, a film version of what was playing in the room and a gallery of the collages I made alongside the installation for people to take home. I might also release the sonic poem at some point.

My sincerest thanks goes to all the incredible music staff at Goldsmiths, especially Heather Britten and Holly Rogers, for their inspiring and thorough academic input as well as their patience and compassion. A special thank you to Jake Reynolds, for the unwavering love and support that made this work possible.

This work was generously supported by the Goldsmiths BME Music Scholar's Fee Waiver.

Installation Documentation

Film Version

Installation Artwork

*************************************************************************************************************

Becoming Time: Thinking and Feeling Time Through Audiovisual-Physical Media

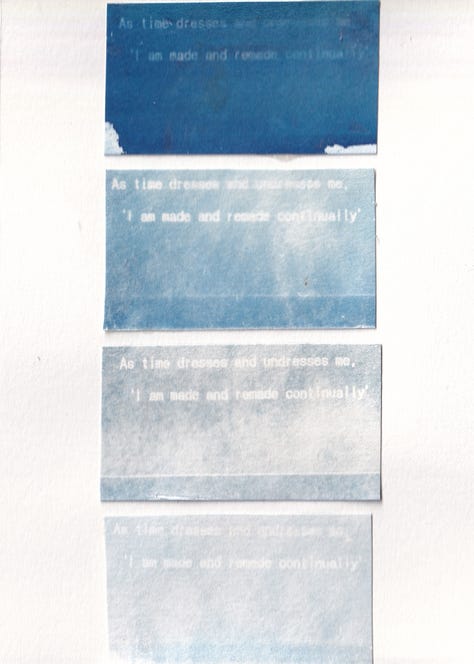

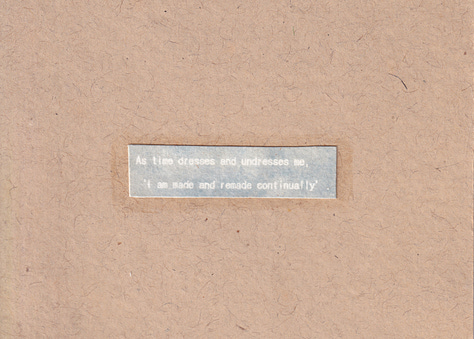

‘As time dresses and undresses me,

I am made and remade continually’

and remade is an audiovisual installation that explores and honours experiential time through multimodal practice research. Engaging with time is crucial to engaging with a diversity of experiences. Clock time methodically permeates every moment of our lives and yet is often overlooked. Upon interrogation, it becomes clear that clock time as it exists today is both a product and agent of colonialism and capitalism. Experiential time on the other hand can be as fluid, layered and malleable as the person experiencing it. Identity shapes experience of time and vice versa. For those of us who follow alternative or fragmented timelines, the rigidity of clock time not only invalidates the fabric of our lives but becomes an oppressive force. And remade at its core is an act of resistance against enforced clock time.

There are many levels on which we, as multifaceted, complex beings, understand and disseminate information. ‘Bringing together the creative and the critical in a reflexive relationship is the function of practice-led research’ and this reflexivity becomes essential to honouring and exploring broad knowledges of time (Grey and Delday, 2011, p. 48). Rather than creating art about my identity and experience of time, and remade is made from a place of my identity and experience of time, becoming a truer representation of who I am than any meta discussion of my identity. Thinking and creating multimodally through my experience of time led me to several artistic renderings which are woven together to create a multiplicitous audio-view of time.

The following practice research questions formed throughout the process of my creative exploration:

How does my experience as a queer, neurodivergent, mixed race person of colour shape my understanding of time?

How can I use the malleable temporality of audiovisual media to manipulate time perception?

How can I unfold the audiovisual out of the screen to explore the materiality of time?

How can I draw from and collaborate with nature to help express malleable time?

My own experience of time is directly informed by my identity. As a mixed race person, the temporal lineage lines that led to my being here are complex and disparate. Intergenerational and fresh trauma fragment my experience of time. My queerness and neurodiversity have placed me on a different, unavoidably slower timeline to that of a heterosexual neurotypical one. Much of my time is spent searching for a timeline that is compatible with my being. My imagined future looks different to the one capitalism had laid out for me and clock time becomes a systemic barrier to that future. Although, I speak as an individual, I know many share my experience. The emphasis on clock time over experiential time isolates and debilitates those of us who are not well enough to perform capitalism, who move at a slower pace and strive towards futures outside of the norm.

Through a fluid understanding of time, the ideas of past, present and future are not separate carriages of a train following each other neatly in succession, but instead are malleable, overlapping, layered phenomena. Botanist and poet Robin Wall Kimmerer contextualises this idea within Native American ways of knowing, saying that ‘time is not a river, but a lake in which past, present and future co-exist’ (2013, p. 343). Rasheedah Phillips, co-creator of Black Quantum Futurism and The Afrofuturist Affair also advocates for a nonlinear approach to time, arguing that ‘in… non binary temporalities, paradox is the tension that holds together space time’ (AfroFuturist Affair, 2022, 23:23). Time is experienced in space and can therefore be approached as something physical. In accordance with this, we can think of time in relation to Tim Ingold’s theory of entangled matter as a ‘meshwork of interwoven lines of growth and movement’ (Ingold, 2010, p. 3) becoming a ‘multitudinous diffraction of agencies’ moving through space (Toksöz Fairbairn, 2022, p. 49). The final installation consists of a surround sound sonic poem, a projected video, an interactive projection sculpture and a series of cyanotype postcards for the audio-viewer to take home with them. It is not only a tapestry of time but a reflective space for the audio-viewer to centre their own unique experience of time.

Time in Nature

Malleable, nonlinear time is abundant in Nature. Deep time can be seen to extend downwards, presenting tangible layers of history as landscape becomes sedimented over time. Robert MacFarlane poetically encapsulates this concept as ‘the dizzying expanses of Earth history that stretch away from the present moment’ (2019, p. 15). Above ground, time is demonstrated through the persistent cycles of growth and decay in Nature. Lichen and fungi ‘liquidate our notions of time’ (ibid., p. 94). Rain falls and is once more evaporated by the sun. Fruit ripens, rots, plants new seeds and the cycle repeats.

Informed by this, my practice is infused with cyclical repetition. In the first iteration of the project, I took my camera and notebook to a houseboat in Mersea on the Summer Solstice to complete a multimodal durational creative process. I wanted to see if a durational time structure could open up new artistic pathways. Every hour for roughly 10 hours over sunset and sunrise, I took audiovisual recordings and wrote poetry in a repetitive process that captured the passing of time through practice. The boat sits on the marshes, where freshwater trickles past it and meets the sea as the tide comes in and out around the boat. Waking with the birds and watching the water enact its cycles on the longest day of the year in windy solitude shaped the prose into an poetic merging of experiential, nature, and clock time (Appendix 1). In the end, I felt the temporal structure of this process was too confining with no way to interact with the future and so moved on to more fluid explorations of time[1].

MacFarlane asserts that ‘deep time opens into the future as well as the past’ (MacFarlane, 2019, p.15). An ‘inertial’ view would see our smallness in the vast sea of time as a get out of jail card of sorts; if we will be gone in ‘the blink of a geological eye’ (ibid., p. 15), then what does anything we do matter? MacFarlane argues that deep time can instead be a reimagining of ‘our troubled present… provoking us to action not apathy’ (ibid., p. 15). Thinking practice through sustainability, Jacob Smith looks to the past at pre-plastic sonic media to serve as a guide for future sonic creation which he calls ‘eco-sonic media’ (2015, p. 1). Following these principals, I built a solar powered cassette player (dubbed ‘the solar cassette’), which has a ‘low impact, sustainable infrastructure’ and ‘facilitate[s] communication with non-human nature’ (ibid., p. 6, 7). To make it, I wired a second-hand cassette player directly to a solar panel via a voltage regulator meaning that the tape slows down at sunset and speeds up at sunrise. In this mutual collaboration, the sun’s rhythm is sonified.

The solar cassette

In his piece Time Zones, Soumik Datta weaves together night and day through combining ‘the night raga Darbari with the morning raga Jaunpuri… to reflect the human spirit’s ability to find home, even when it’s scattered across continents’ (Datta, 2024). Dawn in India is midnight in London; by combining these Ragas, he bridges the gap between time zones, weaving together layers of time to capture a multiplicitous experience (S. Datta, personal correspondence, September 16, 2024). In the second iteration of the project, I recorded the birds in my local park at dawn with the intention of putting the recording through the solar cassette in the evening, so as to merge dawn and dusk in a similar layering of time. In the end, however, I felt that it did not emphasise the audiovisual strongly enough. Following this experiment, I took the poem from the boat, fragmented and rearranged it into a more cohesive work and looped it over the birdsong. The final piece was half an hour long to fit within the temporal confines of the tape. I then recorded a slowing down version of the poem at sunset and a speeding up version of the poem at sunrise, and layered them together with the original recording of the poem. Artists Mendi and Keith Obadike have described the sun as ‘the oldest metronome’ beautifully capturing humanity’s temporal link to the sun (Obadike and Obadike, 2022). Using audiovisual repetition in their sound video, The Sun, Mendi and Keith Obadike seek to conjure the pulse and constancy of the sun as it guides us across time (ibid., 2022). Similarly, and remade is designed to be looped to represent the persistent pulse of the passing days.

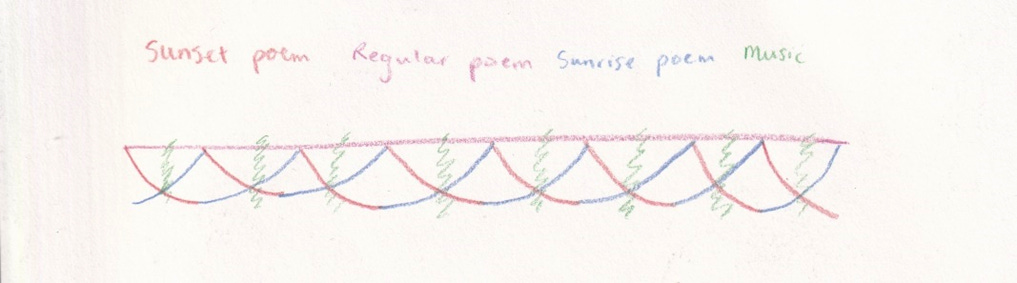

Diagram of changing speeds

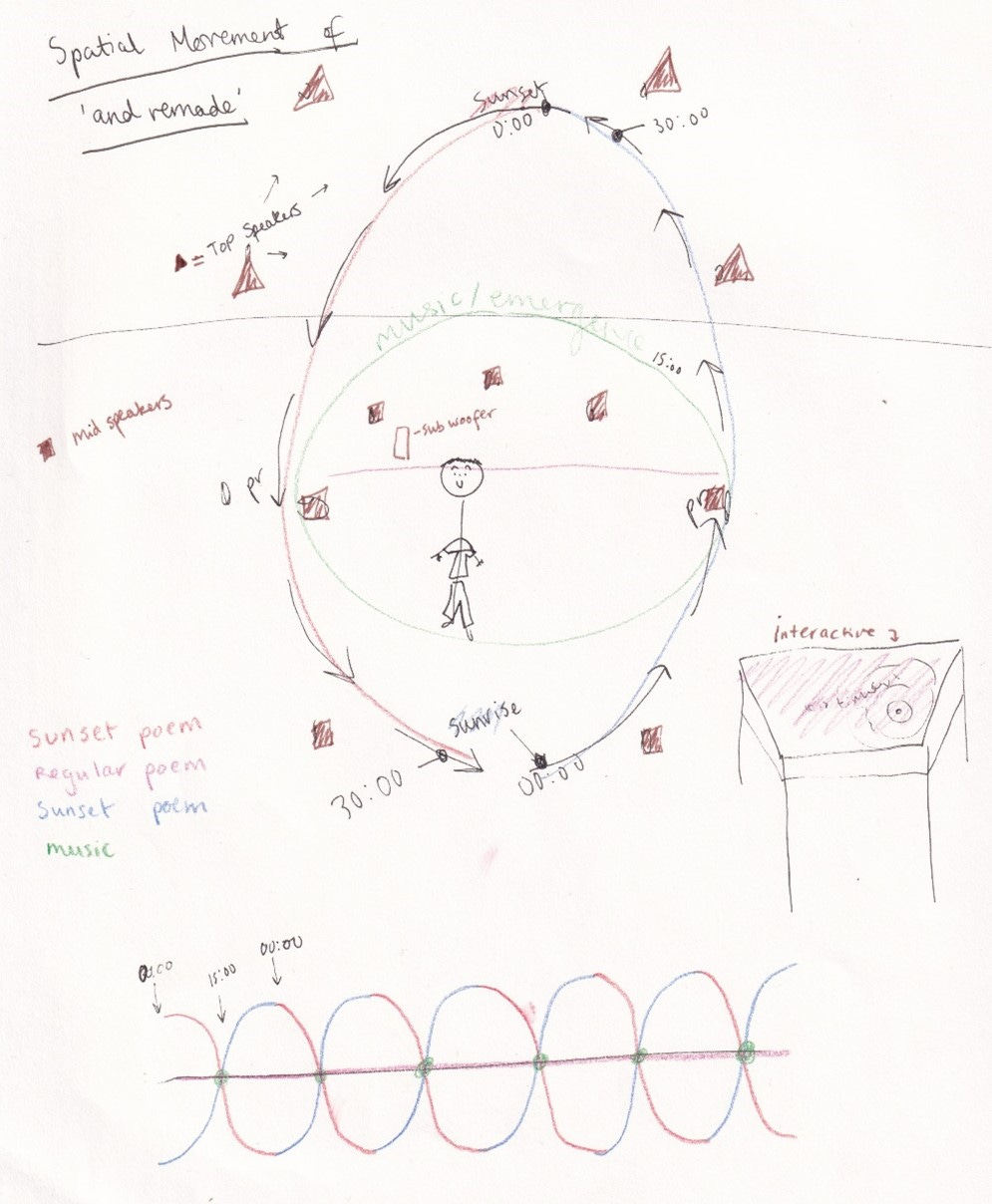

The rhythm of the sun is also represented spatially, making use of Dolby Atmos Immersive Audio to allow the sonic poem to chart a similar movement to the sun across the sky. Initially, I wanted the poems to move in line with East and West but it was at odds with the speaker placement in the room. Instead I opted for the movement to be East and West of the audio-viewer when facing the large screen, which was more affecting as it centred subjective experience. The sunset audio started at the top and descended to the West, and the sunrise audio started at the bottom and rose to the East. The regular speed audio remained roughly in the middle, as did the music. This created an almost imperceptible movement of sound in the room mirroring that of the sun across the sky. The surround sound 3-Dimensionalised the space, drawing together the two screens by sonically enveloping them. As well, the audio-viewers could walk around and hear different elements come through to personalise their experience. The audio of the accompanying film version of and remade is a binaural rendering of this spatialisation so should be listened to with headphones.

Diagram of spatial movement

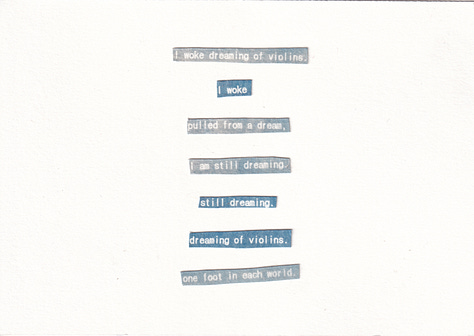

The addition of music creates a wave-like structure and serves to morph time perception through rhythm. ‘Listening alters our sense of time’, Obadike and Obadike theorize, as ‘one of rhythm’s gifts is its ability to reorient us in relation to time and space’ (2022). This applies to both listening and creating music. During the slow, oftentimes overly theoretical creation of the sonic poem, I had an instinctual urge to add violin. Time went from being painfully slow to running like an excited stream; ‘a moment is the senses singing beyond thought’ (Appendix 1). In Being Time, Jenny Gottschalk explores how rhythmic repetition alters perception of time by analysing Toshiya Tsunoda’s O Kokos Tis Anixis. Tsunoda loops small sections of field recordings, sometimes up to 100 times, within the larger recording to break linear notions of time. Gottschalk talks of perceiving time vastly differently, depending on the type of loop- ‘some loops interrupt the flow. Others seem to extend and envelop the space’ (2018, p. 129). The music in and remade unifies the sonic poem as a loop in itself, and also inserts short musical loops that suspend time though repetition.

The sonic structure is replicated visually. My focus on the sun and fluidity of time led me to film reflections on water in a visual abstraction of the sun. I filmed from a small motor boat, keeping the water as still as possible at first and eventually, gradually speeding the boat up. The reflections of the sun(s) diffract as the water moves, visualising time’s multiplicity. The video is then reversed, creating a visual swell through the motion of the boat. To replicate the sonic phasing, I duplicated the video and gradually slowed it down. At the beginning and end, it plays alongside the original video, but in the middle the two videos merge and fill the screen drawing the viewer in. As well, a video of birds that I filmed in Mersea overlays to create a sense of movement and disorient the visual space. The overall structure of and remade is an undulating cycle made of micro cycles moving at different speeds. Indeed, the whole world can be seen as a multitude of pulses; ‘Ice breathes. Rock has tides. Mountains ebb and flow. Stone pulses. We live on a restless earth’ (MacFarlane, 20, p.17). And remade makes use of audiovisual simultaneity to weave together our own sense of pulsing time with the rhythms of Nature.

Native American thinking posits that we are entangled in a loving relationship with Nature. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Wall Kimmerer puts forward the idea that we exist not into opposition to Nature, but as a part of it, ‘linked in a co-evolutionary cycle’ (Wall-Kimmerer, 2013, p. 124). This entanglement is beautifully encapsulated in the Three Sisters Native gardening practice, whereby squash, beans and corn are grown together resulting in a much more fruitful yield (ibid., p.131). ‘The lessons of reciprocity are written clearly in a Three Sisters garden’, serving as a ‘blueprint for the world, a map of balance and harmony’ (ibid.). Our entanglement with Nature is also written into ‘the language of chemistry’ (ibid., p. 344). Wall Kimmerer makes poems out of the facts of respiration and photosynthesis, asserting that ‘the very facts of the world are poems. Light is turned to sugar’ (ibid., p. 345).

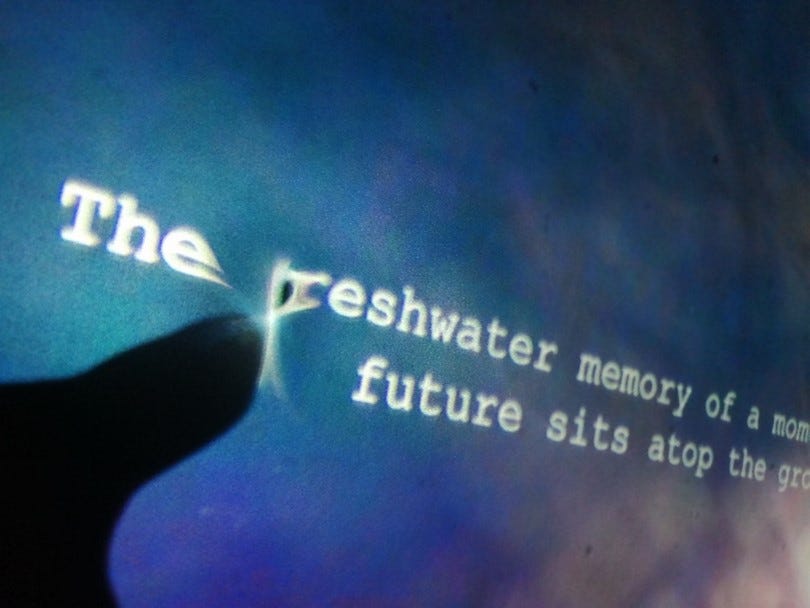

In a similar way, the audio-viewer becomes entangled with the installation when touching the interactive projection sculpture [2]. A video of the regular speed sunlight video and the slowing down sunlight video are overlayed with the text of the poem moving in time with the regular speed poem. This video is projected upwards through a thin layer of water onto a rear projection screen. When the audio-viewer touches the water, the image ripples and the text bends. The audio-viewer becomes part of the ecosystem of the installation.

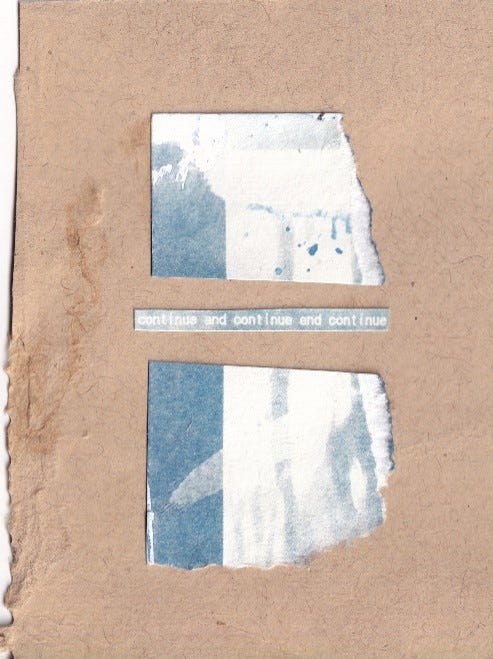

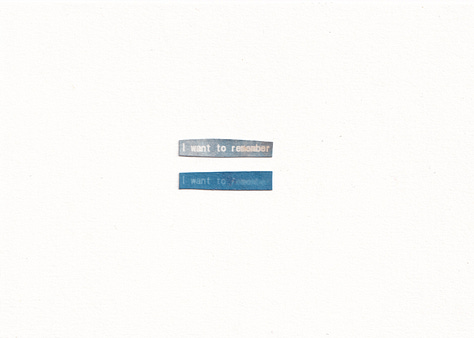

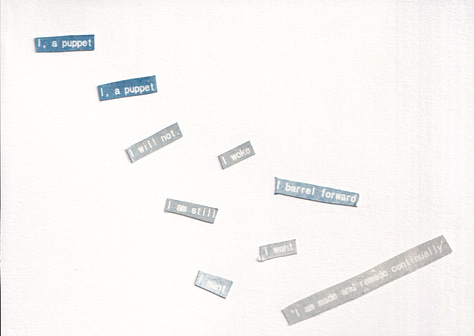

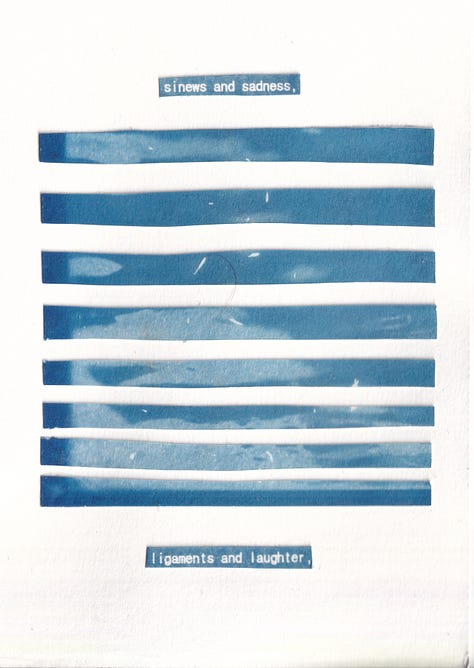

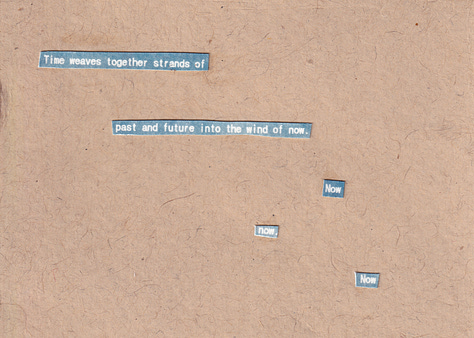

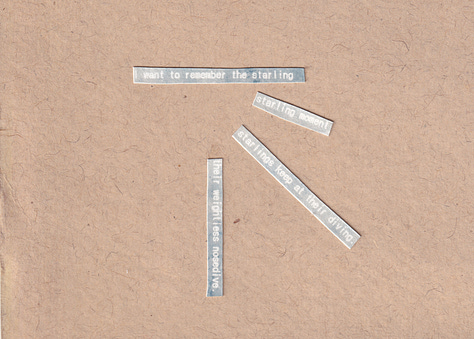

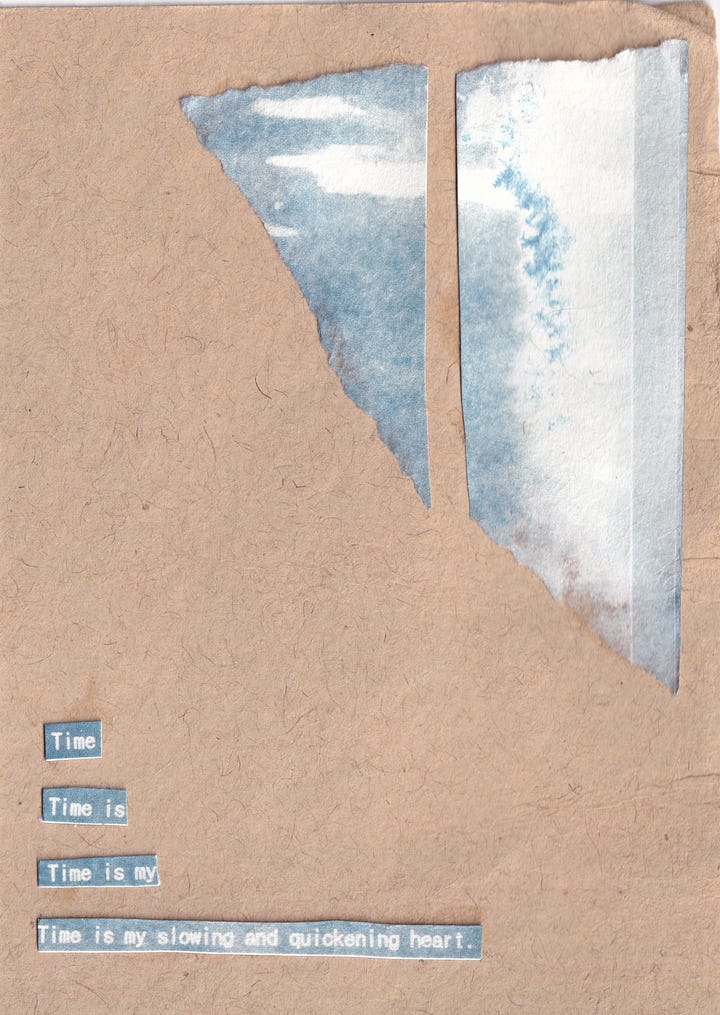

Finally, I made 20 postcards for audio-viewers to take away with them. These were made out of cyanotypes- a method of developing photography with the sun. Initially, I intended to print the programmes as cyanotypes but not all the text was legible. Instead I remediated the cyanotype poems and stills from the film into 20 unique collaged postcards[3]. Thus, the slow temporality of the sun to moves through every part of and remade, from process to beyond the space time confines of the installation room, diffracting in its remediation.

Time in Nature can be seen in cycles of growth and decay, respiration and photosynthesis, and deep time sedimentation, all moving at vastly different speeds. The unbending imposition of clock time over experiential time and Nature time is indicative of the dangerous rift opening up between humanity and the earth, and humanity with itself. Centring experiential time is by default a centring of Nature time as we, in our cycles of growth and decay, are intrinsically entangled with the Natural world. To fully understand the importance of experiential time and Nature time, we must also understand the history of clock time and its implications of the present and future.

Clock Time

If time is a phenomenon beyond human control, then timekeeping is a practical attempt at measuring ‘the time interval between two indices’ (De, 2022, p. 942). There are many examples of clocks throughout history that incorporate natural materials to track time, such as sundials, water clocks, incense burning, sandglasses and charting stars. The physical and multisensory nature of these methods of time keeping demonstrate an enmeshment with the natural world, that has perhaps been somewhat lost as time keeping has become smaller, more accurate and more individual with the delocalisation and digitalisation of time. The installation itself is an homage to this, structuring its wider cyclical movement on the rhythm of the sun and generally working with nature to re/present time.

‘Clocks play a unique role in civilisations’, posits David Rooney, as they bring to light the priorities of a society and the people who govern that society (Long Now Foundation, 2021, 01:13). He uses the word clock to refer to any timekeeping device from sundials to crowing roosters. Roony politicises the clock, arguing that clocks are not only used to control the masses but have also been repeatedly resisted by the masses throughout history (ibid., 04:40). In 263BC, Manius Valerius Maximus erected dozens of public sundials across Rome so as to ‘regulate and control the myriad daily activities of Rome’s citizens’ (Rooney, 2021, p. 13). This was not popular with the public, and playwright Plautus remarked ‘when I was a boy, my stomach was the only sundial, by far the best and truest compared to all of these [sundials]’ (ibid., p. 13). Despite the public’s feeling of oppression, timekeeping in Rome became only more accurate with the eventual addition of water clocks which kept time at night as well as day (ibid., p. 14). Rooney uses this and countless other examples to demonstrate how clock towers have represented the enforcement of order from ruling powers for millennia across the globe. Understanding this can encourage us to think beyond the clock to who is controlling us and why (ibid., p. 8).

And remade has the potential to be a collective experience and highly subjective experience, mirroring both global and local modes of time. Audio-viewers who sit and watch the film alongside others experience a largely shared temporality. But audio-viewers also have the ability to interact with space as they please; moving around the room brings different components of the sonic poem forward, and interacting with the sculpture allows for a direct shaping of the present moment which ripples into the future. Together these possibilities create an audiovisual agency which allow for a decidedly individualised temporality. As well as this, and remade opens a space where experience of time is centred, thus allowing the audio-viewer to reflect on their own relationship to time outside of the pressures clock time.

The shift from ‘solar time and other local-time reckoning methods’ to the global imposition of standard time is closely linked to colonialism, says Phillips (2021, p. 20). In 1884 at the International Prime Meridian Conference (IPMC), a supposedly global committee decided that the Greenwich Observatory was to become the Prime Meridian. The committee was dominated by countries from the continents of Europe and America, with the only Asian country being Japan and the only African country being the newly formed American colony of Liberia (ibid., p. 21). The decision to make Greenwich the longitudinal 0 only reinforced the colonial powers of the select countries on the IPMC committee. Phillips argues that ‘setting the zero point for the world’s time was an… institutionalization of a God-like infinite power over time and space’ within the colonial Western system of power (ibid., p. 20).

As part of her project Time Zone Protocols, Phillips held a Prime Meridian Unconference in order to interrogate and rethink the ‘the creation of written and unwritten political and social agreements, protocols and rules underlying Westernised time constructs (such as Daylight Saving Time)’ (ibid., 25). The unconference operated from a space of ‘black temporal abundance to develop new rituals, new protocols, new guidelines, new shared agreements for time and temporal realities that privilege the time, the timelessness, the space, the spacelessness, the joy, the health, the happiness and the liberty of black people’ (AfroFuturist Affair, 2022, 30:00). In holding Greenwich Mean Time accountable for restricting Black people’s ‘access to and agency over the temporal domains of past, present, and the future’, Phillips spearheads a movement towards opening up new space and time for liberation of the oppressed (Phillips, 2021, p. 25). Bringing forth fluid experiential time highlights the ever shifting distance between it and rigid clock time. Exploring time through nature and artistic practice, for me, became a source of comfort and an exercise in self-acceptance; I might not thrive under clock time but I can tune into a temporality under which I do thrive. And remade seeks to forge a space for experiential time and in doing so validate disparate temporal experiences.

Experiential Time

Studying experiential time becomes a way of verifying our intrinsic experience of the world and moves us towards holding clock time accountable for erasing that experience. In our everyday lives, standard clock time happens whether we like it or not, moving past us or dragging behind us. Subjective time on the other hand is described by Marc Wittmann as a net which holds phenomena such as emotions, memories and sense of self, concluding that ‘we are time’ (2016, p. xii). In his book, Felt Time: the psychology of how we perceive time, Wittmann considers the ways in which time becomes subjective and the impact this has on our relationship to the world and ourselves. Time is physical insofar as it is not only indicated to us by the changing environment but it is also deeply situated in the body; ‘change tells us that time is passing’ (ibid., p.124). A 1970’s psychological study by John C. Lilly found that when a person is put in an isolation tank, most senses are muted almost entirely, yet the sense of passing time persists (ibid., p. 123). Due to the variation in perception of time among participants, he concluded that temporal perception is not only measured through smaller, bodily change, but is linked to consciousness (ibid., p. 125).

Considering the body as a clock, what are an individual’s hour, minute and second hands made of, and how do the rates of rotation vary from the societal clocktower? What are the body-clock arms pointing at? Both physical and theoretical orientation is crucial to phenomenological thought and therefore must be paid attention to. Sara Ahmed makes the case that the physical orientation of queer bodies is different to that of the heteronormative orientation (2006, p. 544). When a child is pressured to follow well-trodden paths towards heterosexual milestones, they become oriented towards an inherited future (ibid., p. 260). ‘Lesbian desires’, however, ‘move us sideways… following rather different lines of connection, association, and even exchange’ (ibid., p. 564). She concludes:

For me, the important task is not so much finding a queer line but asking what our orientation toward queer moments of deviation will be… A queer phenomenology would involve an orientation toward queer, a way to inhabit the world that gives “support” to those whose lives and loves make them appear oblique, strange, and out of place. (ibid., p. 570).

Speaking of the philosopher’s preoccupation with the writing table, Ahmed points out that ‘the objects that we direct our attention toward reveal the direction we have taken in life’ (ibid., p. 546). We can think of time in a similar manner; how do our remembered pasts and imagined futures orient us in the present? In her book Towards a Poetic Memory of the Bengal Partition, Lagnajita Mukhopadhyay sets forth a new approach to understanding ‘diasporic consciousness that emphasises imperfect and poetic memory as the only way to capture fragmentation to produce futurity’ (2023, p. 21). She discusses the long Bengal partition that led to ‘one of the largest mass migrations in history’, lasting decades (ibid., p. 31). For a displaced diaspora whose ‘collective experiences of refugeehood’ have gone undocumented, the narrativization of the past becomes fragmented. Memory becomes something untethered from the simple linearity of the past-present-future line for trauma survivors, leading to a sense of being locked out of the present and, consequently, an unstable identity (ibid., p. 38). Generational trauma compounds this, further fragmenting narratives of memory across centuries.

I relate to this through my own heritage as a mixed race person. Trauma is deeply woven into my lineage lines which are disparate and in many places invisible to my eye. My maternal Jewish Great Grandmother fled the Nazis and raised my Grandfather as Catholic. My paternal Indian Grandparents moved to the UK from farms in Mangaluru and held their children at arm’s length from their culture, telling contradictory stories of how they came to be here. Histories linger, ‘becoming part of the blood stream’ (Silvers, 2024). The writing of this essay prompted discussions with my Father about his parents and I have learned new stories about the lines that led to my being here. Where memories are suppressed due to trauma, narratives of heritage become fragmented. I think of the becoming lines that led to my being here as a ‘diffraction of multitudinous agencies’ (Toksöz Fairbairn, 2022, p. 49). These lines extend towards now from disparate places in space and time, complicating my heritage narrative. Similar to Ahmed’s queer orientation, racial identity is not always given; as a mixed race person ‘you have to sit and ask where you fit in’ (Silvers, 2024).

Poetry, then, becomes an essential tool for reprocessing the past and reshaping the future, as ‘a poetic approach can better address the fragmentation and displacement of disordered experience’ (Mukhopadhyay, 2023, p. 25). Although the poem in and remade is not directly about my mixed race heritage (or any other identity), it is important to recognise how my fragmented and disparate self has deeply affected my perception of time, physically and emotionally. In the remediation of the poetry, fragmented experience of time becomes fluid. Poetic fragments find new dynamic multimodal paths outside of clock time as the words diffract multitudinously outwards. They began from a durational meditation on felt time, they moved from page to air in the speaking of them, they became temporally and sonically shaped by the sun, they moved and vibrated around the installation room, they are written to be touched and abstracted, they are printed with the sun and finally taken home by the audio-viewer. The coinciding audio, visual and physical remediations of the text in and remade 3-dimensionalise linear time, blurring the boundaries between our ideas of past, present and future. Poetry becomes a vessel through which time comes alive, making simultaneous malleable timelines tangible.

Time, Boredom, Repetition and the Audiovisual

Although digital audiovisual media is quite literally tethered to a timeline, it can also vastly change perception of time. The audiovisual potential for synchronicity allows for a weaving together of many temporalities. In and remade, these are:

Time affected by nature, via the solar cassette.

Time affected by human touch, via the interactive projection sculpture.

Time as movement through space, in slow moving surround sound.

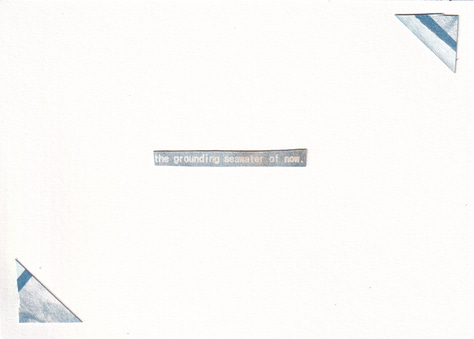

Time as layered (‘The freshwater memory of a moment, a freshwater vision of the future sits atop the grounding seawater of now’), through the layered video.

Durational/deep time, represented through the cyanotype postcards which change over time.

‘Sound can exert considerable influence’ on temporal perception of moving image (Chion, 2019, p. 12). In mainstream cinema, music creates immersion by ‘stitch[ing] together filmic elements to create a more coherent visual flow’ (Rogers, 2017, p. 203). In the case of audiovisual installation, ‘by taking over an entire room, video work can immerse its visitors completely.’ (Rogers, 2014, p. 20). But what of the audiovisual work that draws the audience’s attention to the passing of time itself? Michael Walsh dubs these ‘durational works’; specifically these are ‘films, videos and installations… that substantially subtract conventional dramatic interest, challenge established expectations of running time and foreground the passage of time as a formal condition of cinema’ (2022, p. 1).

By Walshe’s criteria, and remade can be considered a durational work; there is no narrative, it can be viewed in fragments or for as long as the installation runs, and through the themes presented it surely foregrounds the passage of time. The slow moving audiovisual progression and persistent repetition seeks to lull the audience into a reflective space. Similarly, Andy Goldsworthy’s piece Standing Still at Dawn (2022) captures a durational practice through durational filmmaking. The video begins with almost 20 minutes of darkness. Slowly, an image of Goldsworthy standing facing the wall of his studio appears with the door open behind him, through which the sun starts to emerge. The video lasts 1 hour and 10 minutes and ends with Goldsworthy walking off, leaving behind just the illuminated patch of wall (Goldsworthy, 2022). This glimpse into his regular practice captures not only the movement of the sun, but the artist’s meditation on it.

Durational cinema has the potential to be extremely boring; most of the films Walsh examines are at least twice the length of a long feature film. But even durational works less than 5 minutes can be boring by design. Chiara Quaranta builds on Heidegger’s thoughts on metaphysical boredom to explore cinematic boredom. The slow audiovisual movement of and remade can be seen as a counter to short form content platforms that prey on ‘the constant need for stimuli to suppress empty time’ (Quaranta, 2020, p. 19). Heidegger’s idea of ‘Profound Boredom’ is a leaning into the experience of boredom in order to allow it to tell us something (ibid., p. 5). Placed in a cinematic context, Profound Boredom ‘opposes the pleasure of mainstream entertainment cinema, where pleasure is the (illusory) being filled up, and replaces it with the pleasure of “being left empty”’ (ibid., p. 19). Quaranta’s discussion of boredom concludes that ‘once the inherent resistance to being bored is overcome, this more or less “long whiling away of time” permits us to think about what we see and how we look at images’ (ibid., p. 20). Profound Boredom can ultimately lead us to a state of ‘Dasein’ or ‘openness for being’ (Hezekiah, 2010, p. 12).

And remade is circular and can be experienced for as long or short as the audio-viewer decides; I wanted to give people the choice to feel bored and the option to leave. Feedback from people who experienced and remade have recounted dynamic experiences of the piece’s temporality. One audio-viewer described the repetition (sans music) as ‘especially challenging’ at first, going on to describe the emergence of music as a reward akin to a psychedelic high, and the resyncing as evoking ‘a huge feeling of satisfaction and relief’ (Appendix 2, audio-viewer 1). Another attendee noted how ‘it felt like the room was just asking you to slow down and think about… the passage and fluidity of time’ (Appendix 2, audio-viewer 4). Most interesting to me was how the installation opened internal spaces; some found it meditative and calming, some made up stories about the images they were seeing, and one audio-viewer even accessed a rare childhood memory (Appendix 2, audio-viewers 1-8).

Thinking philosophy through film affords filmmakers and academics alike the ability to insert simultaneity into multifaceted concepts such as being, consciousness and time. In her book Phenomenology’s Material Prescence: Video, Vision and Experience, Gabrielle A. Hezekiah explores the work of Trinidadian artist Yao Ramesar’s films. She engages with his aesthetic, ‘Caribbeing’ whereby Ramesar ‘seeks to jog the audience’s memories of the deep past, removing the veil imposed by the colonial experience’, contextualising this within Heidegger’s concept of ‘Dasein’ (Hezekiah, 2010, p. 10). Ramesar’s film, Journey to Ganga Mai, is ‘an encounter with timelessness’ (ibid., p. 72). The video utilises repetition- both in editing which moves ‘forward and into itself’, and the mantra which sounds throughout- to ‘heighten the experience of Temporality’ (ibid., p. 69). The effect is a video in which ‘we feel our Consciousness enduring. Circularity and repetition allow us to believe that it is time rather than the event that is unfolding’ (ibid., p. 71). Thus, circularity and repetition can lead us to a state where we are able to transcend linear clock time.

Repetition has the potential to be both boring and immersive, manipulating our awareness of clock time. I have used repetition to shape the pacing of and remade. On a loop, the piece can be seen as an undulating temporal wave built by different repetitions, with time moving most slowly when the poetry is synced up, and moving most quickly when the music is at its climax and the birds appear. The poem repeats but takes on new meaning as it starts to talk over itself and the repetitive music dramatically shifts temporal perception.

There are two types of sonic repetition in and remade. First is the pulseless repetition of words, and second is the wordless pulse of the music. When the words are slowly un/syncing, time drags and the audio-viewer is placed in a space of Profound Boredom. The unchanging version of the poem can be seen as a representation of clock time. The sunrise and sunset versions of the poem can be seen as sonifications of Nature/experiential/malleable time. It is not that the sun poems move towards and away clock time, rather we can see all three poems moving to open a space for Dasein. When the three poems are at their most out of sync, a gap opens for music to emerge representing a space of becoming. Obadike and Obadike posit that ‘a repeating pulse can cause us to lose our grip on the passage of time’; the repetitive music in and remade aids in suspending time (2022). The dancing sun is a slowly shifting ‘visual micro-rhythm’, creating ‘rapid and fluid rhythmic values, instilling a vibrating, tremulous temporality in the image’ (Chion, 2019, p. 15). As well, the visual frame widens, drawing the audio-viewer in. This musical repeating pulse in combination with the visual micro-rhythm and the repeated clip of the birds places the audio-viewer in a trance-like state where ‘time completely disappear[s]’ in an ‘infinite space’ (Appendix 2, audio-viewer 2, 5).

Time Made Physical

In his paper Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials, Ingold suggests that the world is made up of entangled lines on ‘continuous trajectories of becoming’ (2010, p. 11). These lines leak, complicating their simple linearity, and becoming instead enmeshed in an alive world ‘continually on the boil’ (ibid., p. 8). Put into the context of Karen Barad’s theory of agential realism, the lines of the world bring each other into becoming intra-actively. Where Ingold replaces ‘objects’ with ‘things’ formed of lines ‘wherein boundaries are sustained only thanks to the flow of materials across them’ (ibid., p. 12), Barad replaces ‘objects’ with ‘phenomena’ (Barad, 2007, p. 139). Intra-action is the process by which phenomena mutually bring each other into being (ibid., p. 33). Thus, ‘space, time, and matter are mutually constituted through the dynamics of iterative intra-activity’ (ibid., p. 181).

The interactive projection sculpture and the cyanotypes can be seen as time made physical. Temporally, blue is a significant colour. Deep glacial ice takes on ‘the blue of time’ (MacFarlane, 2019, p. 339). Red, the least stable colour, fades to blue over time. The artist, Lauren Heckler, collects previously red pictures from charity shops because ‘even though they’re different in style and subject, the blueness links them, and the movement of time is brought to focus’ (Private correspondence, Appendix 3). Rebecca Solnit explains that

Blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water. Water is colorless, shallow water appears to be the color of whatever lies underneath it, but deep water is full of this scattered light, the purer the water the deeper the blue (2006).

Although largely stable, when exposed to sunlight for some years, the blue of a cyanotype will begin to fade to white. This change is reversible, and the blue can be restored if placed in a cool dark room (Ware, 2020, p. 271). In 1973, Tony Conrad reframed moving image with his piece Yellow Movies. The film, which consisted of cheap yellow paint on canvas, was set to last 50 years as the paint changed slowly over time (Conrad, 1973). In a similar way, the postcards available for the audio-viewer to take home in and remade act as indeterminate durational moving images which weave into the future. The postcards represent a ‘diffraction of multitudinous agencies’ (Toksöz Fairbairn, 2022, p. 49), reacting uniquely to the lives they become a part of.

A postcard that I found in my scanner one month after the installation.

The interactive projection sculpture represents a physical relationship with time. In their paper, On Touching- The Inhuman That Therefore I Am, Barad challenges the miniscule gap between ourselves and all that we touch. When touching a mug, for example ‘you [might] feel the smooth surface of the mug’s exterior right where your fingers come into contact with it… but what you are actually sensing, physicists tell us, is the electro-magnetic repulsion between the electrons of the atoms that make up your fingers and those that make up the mug’ (Barad, 2012, p. 3). This explanation presents a void between two points. Barad recontextualises this idea within quantum physics, radically queering the classical explanation of particles and touch. Instead the void becomes ‘no longer vacuous’ but instead ‘a living, breathing indeterminacy of non/being’ (ibid., p.210).

Conclusion

and remade is not only brought into the alive present but implicates futurity in the ripples created by the body of the audio-viewer. The text on the interactive projection moves in time with the clock time version of the poem. It bends when touched, in a way drawing together and completing the audiovisual poem. Robyn Stilwell talks of ‘travers[ing] the gap’ between diegetic and non-diegetic, arguing that ‘the border region—the fantastical gap—is a transformative space, a superposition, a transition between stable states’ (2007, p. 200). Taking this sentiment into the context of the predetermined screen, the interactive sculpture allows the audio-viewer to traverse the fantastical gap between them and the artwork, and between ‘immobile’ and mobile as they become a part of the installation (Friedberg, 1993, p. 134). As well, the reflective space between water and light becomes a ‘diffraction of multitudinous agencies’ (Toksöz Fairbairn, 2022, p. 49); light explodes both in the video itself and as the water is moved by the audio viewer. Through interacting with the sculpture, time itself becomes touchable, visible in ripples and refractions. These spaces that open up between points (sun and water, body and word, clock time and fluid time) can be seen as emergent spaces of becoming. We can consider the distance between all dichotomies similarly; when we complicate binary modes of thinking, when we refuse to be one thing or the other, a space of becoming can emerge.

Time unfolds out of the screen/speakers in and remade and becomes physically entangled with the becoming here and now. In the audiovisual temporal shift where music emerges and the screen expands, lily pads appear on the screen for the briefest of moments disorienting the viewer; a moment of tangibility in a sea of abstraction. This moment might represent humanities brief becoming in the vast expanse of deep time. The creation of and remade has allowed me to form new relationships with my experience of time, of time in nature and thus with the space of becoming that exists within. Recentring experiential time becomes a radical undoing of oppressive clock time. Internal and external spaces of becoming open, honouring the multiplicity, nuance and fluidity of divergent experience.

Bibliography

AfroFuturist Affair. (2022, May 13). Time Zone Protocols - Prime Meridian Unconference: Opening Assembly [Video]. YouTube.

Ahmed, S. (2006). Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 12(4), 543-574.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Duke University Press.

Barad, K. (2012). On Touching— The Inhuman That Therefore I Am. d i f f e r e n c e s: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 25(3), 206-223. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943

Chion, M., & Gorbman, C. (2019). Audio-vision : sound on screen (Second edition.). Columbia University Press.

Conrad, T. (1972). Yellow Movies. [Moving Image]. MoMa, New York.

Datta, S [soumikdatta]. (2024, June 21). Instagram.

Dee, S. (2022). Sundial to the Atomic Clock. Resonance, 27(6), 941-959.

D'Souza, F. (2024a). Freda's Substack. Substack.

D'Souza, F. (2024b). Building an Interactive Projection Rig. Substack. https://fredadsouza.substack.com/p/building-an-interactive-projection

D’Souza, F. (2024c). and remade Installation Postcards. Hotglue.Me.

https://fredadsouza.hotglue.me/?%27and+remade%27+Cyanotypes.head/

Friedberg, A. (1993). Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern. University of California Press.

Goldsworthy, A. (2022). Standing Still at Dawn. [Video]. https://andygoldsworthystudio.com/standing-still-at-dawn/.

Gottschalk, J. (2019). Granulated Time: Toyisha Tsunoda's O Kokos Tis Anixis. In R. Glover, J. Gottschalk, & B. Harrison (Eds.), Being TIme: Case Studies in Musical Temporalities (pp. 113-130). Bloomsbury Academic.

Gray, C., & Delday, H. (2011). A 'Pedagogy of Poesis'. Acoustic Space, 9, 45-58.

Hezekiah, G. (2010). Phenomenology's Material Presence: Video, Vision and Experience. Intellect.

Ingold, T. (2010). “Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials.” Realities. Scotland: University of Aberdeen, 2010.

Long Now Foundation. (2021, September 21). A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks | David Rooney [Video]. YouTube.

MacFarlane, R. (2019). Underland : a deep time journey. Penguin Books.

Mukhopadhyay, L. (2023). Towards a Poetic Memory of Bengal Partition. Tandra Chakraborty.

Obadike, M., & Obadike, K. (2022). Our Statement for introducting The Sun for Time Zone Protocols. timezoneprotocols.space. https://timezoneprotocols.space/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Obadike-Statement-for-TZP.pdf

Phillips, R. (2021). Unmapping Black Temporalities. The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies, 36, 20-25.

Quaranta, C. (2020). A Cinema of Boredom: Heidegger, Cinematic Time and Spectatorship. Film-Philosophy, 24(1), 1-21.

Rogers, H. (2014). Spatial Reconfiguration in Interactive Video Art. In K. Collins (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Interactive Audio (pp. 15-30). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199797226.013.001

Rogers, H. (2017). Audio-Visual Dissonance in Found Footage Film. In H. Rogers, & J. Barham (Eds.), The Music and Sound of Experimental Film (pp. 185-204). Oxford University Press.

Rooney, D. (2021). About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks. Penguin Random House UK.

Silvers, I. (2024, August 05). Ben Bailey Smith: “As a mixed person, you’re not allowed nuance”. Mixed Messages. https://mixedmessages.substack.com/p/ben-bailey-smith-mixed-race

Smith, J. (2015). Eco-sonic media. University Of California Press.

Solnit, R. (2006). A Field Guide to Getting Lost. Penguin Random House.

Stilwell, R. (2007). The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Nondiegetic. In D. Goldmark, L. Kramer, & R. Leppert (Eds.), Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema (pp. 184-202). University of California Press.

Toksöz Fairbairn, K. (2022). dis/cord: thinking sound through agential realism. punctum books.

Wall Kimmerer, R. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

Walshe, M. (2022). Durational Cinema: A Short History of Long Films. Springer International Publishing.

Ware, M. (2020). Cyanomicon- History, Science and Art of Cyanotype: Photographic Printing in Prussian Blue. Self Published. https://www.mikeware.co.uk/mikeware/downloads.html

Wittman, M. (2016). Felt Time: The Psychology of How We Perceive Time. The MIT Press.

Appendix 1: Poem

It is time that holds me upright, and I, a puppet of the present (with all its demands and graces) continue and continue and continue existing until I will not.

It is time that holds me upright, and I, a puppet of sinews and sadness, ligaments and laughter, wave to the past and bow the future.

*

I woke dreaming of violins.

Now the distant echoes of birds make me feel as though I am still dreaming. What separates one moment from the next? Perhaps they bleed and stretch over eachother like the split second you are pulled from a dream, one foot in each world.

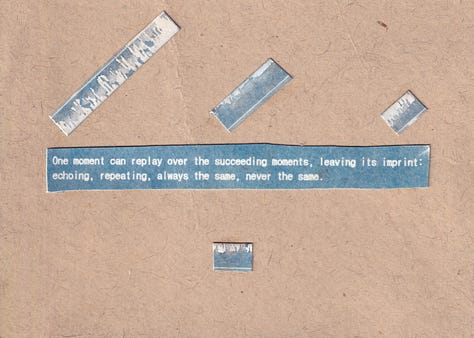

One moment can replay over the succeeding moments, leaving its imprint

Echoing

Repeating

Always the same

Never the same

What separates layers of time?

Perhaps it is like freshwater that runs into the sea and sits atop the salty water. These different densities of water remain separate but mingle where they meet.

Time is multiple

Time is malleable

Time weaves together strands of past and future into the wind of now

Time is the rising and setting sun

Time is my slowing and quickening heart

Time is the rotting bread and the budding flower

Time experienced as a cardigan hugged tight

Time experienced as the vast blanketed sky

Time expanding and contracting through the long short days

Time is the communing birds

Time is my persistent sadness

Time is my unbearable joy

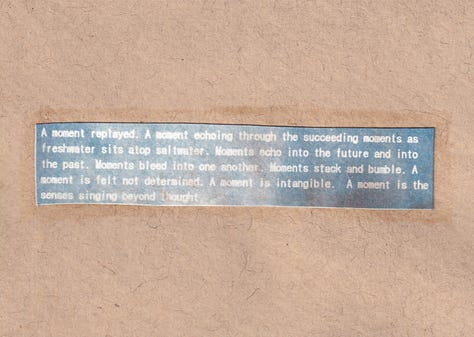

A moment replayed. A moment echoing through the succeeding moments as freshwater sits atop saltwater.

Moments echo into the future and into the past.

Moments bleed into one another.

Moments stack and bumble.

A moment is felt not determined.

A moment is intangible.

A moment is the senses singing beyond thought.

I want to hold a moment in my hands. I want to remember the starling swell so vividly that I am among them in their weightless nosedive. The starling moment is gone but remains imprinted as I barrel forward into the next moment and the next, in some linear notion of time. But time is not linear. The freshwater memory of a moment, a freshwater vision of the future sits atop the grounding seawater of now.

Meanwhile the starlings keep at their diving.

*

As time dresses and undresses me,

‘I am made and remade continually’.

Appendix 2: Experiences of the Install

Audio-viewer 1

For me personally, the installation was first and foremost an experience that paralleled a psychedelic experience. Apart from the fx implemented which relied on light distortion and fragmentation, the repetition became very ‘out of body.’ At a certain point this repetition felt especially challenging and, to continue on with the psychedelic metaphor, felt like a ‘come up.’

Then, all at once, our patience was rewarded and our hypnosis was broken with beautiful string melodies and delicate variations—the come up lead to a peak of audiovisual stimulation. The foliage that swept by felt supernatural, the birds felt alive and in the room, and the water’s hues felt alien—and of course the black and white split screen aided with these intermittent cycles of disorientation and elation. It was especially emotional and felt like meditation. The waiting (which felt out of time) and disciplinary watching and listening paid off.

The plant life streaming across the stream and birds were very powerful and realistic images for me, like those plants felt / looked like I was on drugs.

Towards the end, what I’ll call the ‘come down,’ I began to anticipate the video looping and wondered if it already had started over. I kept analysing minute details to try and compare them with the start of the film. After minutes of stimulus overload and elation, I was a bit confused again. When the film did conclude, as with most repetitive and minimalist works, a huge feeling of satisfaction and relief hit me immediately.

Throughout these more ‘in-between’ moments, I wandered to the projector-pool object in the back of the room. The interactions with the ripples felt childlike but equally psychedelic.

I also appreciated how analogue everything felt. It didn’t feel overly digital or artificial. The natural imagery was of course edited, but still felt organic. The watery projector aided with this analogue feeling and the simple and straight forward split screen/lack of hard and complex cuts also helped maintain an authentic/organic environment.

Also! Just remembering I was so curious about this moment. Where and when was it? Was the audio linked or separate? I was making up this intimate story on a boat’

Audio-viewer 2

‘I really enjoyed your installation! To be completely honest, I was sceptical when I first walked in. It took me some time to understand how the different elements connected thematically, aesthetically, and physically. However, having moved around the space for a short amount of time I found myself totally immersed. I particularly liked the slow, almost imperceptible introduction of the string music into the soundscape – it was at that point which I felt my sense of time completely disappear. Even a week or so later, I cannot say how long I was in the installation, it could have been any length of time from 15mins to an hour!’

Audio-viewer 3

‘When the reflected sunlight in the water began to multiply and dance brightly - I was reminded of something from my earliest years as a child that I'd forgotten for many years (but had remembered during a very particular occasion a few years ago) and which your film caused me to re-remember... i.e. it's only the second time I've remembered that I had that memory. The reason is because of the way the sunlight was acting in the video, as that's what the original memory is centred around. What I'm driving at here is that memories (and perhaps time) are not simply streams of words or numbers, they are also encoded with 'circumstance', the environment and feelings around the event that then become incorporated into a memory, and which one can unexpectedly unlock with things like sunlight dancing on water.’

Audio-viewer 4

‘I think it was beautiful to be a part of and to witness your installation mostly because it was just so calming, it felt like being transported into a different place where time didn’t move but also kept looping when I walked into the installation room if that makes sense ??

I think when I first walked in and sort of adjusted to the setting, I tuned into the poem just as one sentence was being read and that one line really stuck with me, I found myself looking forward to certain phrases and certain sections of the music which was really fun because each time it looped it felt different but still familiar somehow which I think is a really nice parallel to how time is experienced, it almost felt like deja vu but not?

I think my absolute favourite part of it was just how serene it was, it felt like the room was just asking you to slow down and think about time and the passage and fluidity of time, I was talking about it with your friend after on the tube back how I was really grateful for that space because I feel like I’m usually thinking about a million things at once but there it felt like walking into the room you were just absorbed by the moment and forced to stop your mind from racing and just really sit and feel the words kind of run through you over and over.

It felt like a lullaby.’

Audio-viewer 5

‘There was a wonderful moment, I think around the time the bass notes started kicking in, or maybe it was before, while I was watching the movement of the water in the right hand panel and the birds flying, and I’m not sure exactly why, but I think the closeness of the water somehow, along with the rapidity of its motion made me think of a line from Hamlet which I hadn’t thought of in a long time; ‘O god, I could be bound in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams’

Just how close the water was, and how much possibility it seemed to hold for something so small, I dunno it made me think of being in a nutshell and being a king of infinite space, I felt like the birds and the reflections of the sun in the water greatly enhanced this effect of seeing so much in something as small as a little stretch of water. There was something else that kept coming to my mind during the experience but I can’t quite remember now what it was.’

Audio-viewer 6

‘When I came into the room, I enjoyed the darkness and the image projected on the wall. The room was crowded with people who came to see the installation, but felt much more spacious when I was free to walk around and explore the water tray. I enjoyed showing new visitors the water tray, who may not have seen it as they came into the room, and enjoyed the curiosity and wonder of their expressions.

I loved the spoken word, and the way certain phrases kept coming back again and again, creating a circular narrative rather than linear. The tripling of the voices also added to the non-linear sense of narrative as phrases were often a few beats behind each other, and one voice was lower, sounding slowed down.

I loved the images that gave a sense of eternity, with water moving and yet seemingly standing still because there was nothing to fix my gaze onto, until the lily pads floated by. The whole installation seemed circular with a development in the middle, created by the addition of music and the lily pad images. This was a grand climax that appeared again and again,as the tape looped round. I was lucky enough to have entered the room in the final part of the loop so didn’t perceive the work as a half hour video, but more as a circular piece. The imagery of flying birds and moving water overlaid also created a sense of eternity as all places were superimposed on top of each other.

I loved the water tray which gave an added dimension to the video. I could play with patterns, starting ripples from opposite ends, tapping different fingers, drumming, and flicking water, all to create different patterns. I could also interact with other people who were creating patterns in the water.

It really helped me to have the spoken word written on the video so I was able to process phrases visually and audially, and again this reinforced the phrases that came back again and again, creating a non linear narrative.

I wish the water patterns made could be projected on to the bigger screen, but I understand there were probably technical limitations. This was the only thing that could possibly be improved on, but it was an amazing installation that left me with a sense of calm and wonder, and a glimpse of timelessness, conveyed in a way that wasn't contrived, vague or pretentious. I left with a deep sense of calm and wonderment.’

Audio-viewer 7

‘I was really taken with how it played with the ways that the present moment can be stretched and squeezed by perception. I wanted to ask you at the time about the layers of voices. Most of the time I had the impression that the slower, more stretched/distorted voices were lagging behind the clear voice with their slower speed, but then at times the order seemed to shift with them in front of the clear voice. I wasn't sure whether this was an illusion or not and found it hard to be certain even as the installation repeated. After being in the room for a while it was hard for me to recall the order of clearer and distorted voices of previous lines, I think maybe because my perception of the present moment felt like it was being stretched. I also had an interesting experience with the video transitions, in particular between the single and double videos. I was practically unaware of some of the transitions until I had realised they had happened after the fact, which was quite startling. This happened both when at the water table and sat down watching the video. On a repeat I was able to catch them changing but I had to do it deliberately otherwise it slipped through my perception like a magician's trick. This gave me the feeling that my perception of time passing had in some sense slowed for a while and then jumped forward when I realised the change had happened, a feeling not unfamiliar to me due to being somewhat time-blind due to neurodivergence.

In the river scene, the sense of time passing seemed concentrated to sections when the camera passed over plants and other distinctive features. I wasn't expecting to be able to stay for more than one repeat but I am really glad I was.’

Audio-viewer 8

‘I lost my sense of time as spoken phrases were recirculated, like echoes. I couldn’t tell if they were being changed slightly or just repeated.

It had the sense of a dreamscape, or the sensation of falling to sleep and existing in that in-between space that is outside of linear time.

There was a moment of soaring violins and expanded moving image where time seemed to grow more spacious, or we escaped time all together.’

Appendix 3: Lauren Heckler on collecting blue

‘I’m fascinated by longing and desire, the passing of time, and also l how we understand and interpret space and place. Desiring space and place beyond our physical embodiment is linked with the colour blue through the physics of aerial perspective, what is furthest away in our sight line becomes bluer. Images / photos also turn blue slowly in the sun, and as their reds fade, a new version of something familiar emerges. But it happens so slowly that it’s pretty imperceptible to the viewer who sees it everyday. Like changes in our bodies. I like having things in my life with a history, and finding objects and clothes in second hand shops that slip freshly into my identity. I wanted to collect faded into blue images from second hand shops because even though they’re different in style and subject, the blueness links them, and the movement of time is brought to focus.’

[1] Much of this process is documented in my practice research diary (D’Souza, 2024a)

[2] The building process is documented in my practice research diary (D’Souza, 2024b)

[3] The full documentation of the postcards can be found online (D’Souza, 2024c)