[c. Jan 2023]

Since moving to Catford, I have to go through London Bridge Station to get just about anywhere in London. As someone who is very easily overstimulated, I find this 10 minute interchange rather stressful, especially navigating my way through so many people in the long passage between the trains and the tube. Nonetheless, in this passage is also my favourite moment of my journey: the public organ. The Henry Jones organ is a beacon in a liminal soundscape, and it has become a personal soundmark in an oftentimes unbearable journey. Centred around the organ in London Bridge train station, this piece captures the shifting from place to non-place, every day to exceptional, and crowd to individual. It displays the contrast between these concepts in real time by shifting back and forth from train station ambience to members of the public playing the organ. This shifting was captured in the recording process as I was able to walk all the way around the organ whilst people were playing, capturing the organ in one half of my rotation and the train station in the other.

London Bridge Station’s refurbishment was completed in September 2018. It transformed a station which was widely considered to be a ‘tangled mess’ (Wilson, 2021) into an award winning piece of architecture (RIBA, no date). The station is filled with Western red cedar diffusion panels (figure 1). Western red cedar is known to help absorb sound, being a less dense wood (Taylor guitars, n.d.), and the panels scatter sound which reduces aggressive bounce back of noise and mellows the soundscape. Because of this, even when busy, the station is never hugely loud or overly echoey.

Marc Augé defines transient spaces that have a sense of anonymity as non-places (2008, Augé). The term is a subjective one, based around an individual’s relationship with a place and whether or not it feels transient to them. According to this definition and to my own relationship with it, London Bridge Station can be considered a non-place. In Acoustic territories: sound culture and everyday life, Brandon LaBelle discusses Anna Karin Rynander and Per-Olof Sandberg’s 1998 installation of ‘sound showers’ in the non-place Oslo Airport (2010, p. 195). Travellers can stand under one of eleven parabolic speakers playing anything from waves to whispered stories. The installation shifts a traveller’s soundscape from liminality to one of deliberate listening and engagement with their audible surroundings. These showers can be considered both a ‘form of distraction’ and a ‘cleansing opportunity’ (La Belle, 2010, p. 195), and the organ in London Bridge station acts in much the same way. Just like in an airport, there is a lot of sound in London Bridge that the average traveller will tune out; from irrelevant tannoy announcements to crying babies. This ‘unwanted sound’ is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary (and widely understood) as noise (Truax, 1999). Against the back drop of a noisy non-place, the sound of the organ stands out as a sound signal, a sound shower of sorts, heavy with cultural and historical connotation.

A church closes almost every day in an increasingly secular UK, their organs disappearing with them (Dawson, 2022, 03:45). Although a few organ building and restoration companies still exist in the UK, their work is largely centred around organs for organisations with wealth such as Cathedrals and Oxford colleges. This is because the ‘organ culture survives at the top end of the church’ (Dawson, 2022, 35:00). However, it is the most ordinary seeming churches that often house organs of historical note, which is why so many end up lost without knowledge of their value (Dawson, 2022, 00:09:20). Organs are indeed historical artifacts, allowing for a sort of sound archaeology, whereby instruments up to decades old can be skillfully and accurately restored to discover something like the sound of their day. Organ maker, Dominic Gwynn describes this process as ‘trying to get the pipes to tell you what they originally sounded like’ (Dawson, 2022, 36:35). Organs can then be heard as Handel, Bach and other people at the time may have heard them (Dawson, 2022, 14:40). The UK has a deep history of organ making but, as organ restorer Martin Renshaw laments, many organs are exported abroad (mainly to France) as there are not enough places in the UK to house restored organs. As a result, he says, ‘we’ve lost our cultural heritage’ (Dawson, 2022, 15:50). Because of the recent acceleration in the selling of churches, the sound of the organ has been lost within people’s lifetimes. Blanche Beer, a 100 year old organist who started playing when she was 12, describes how the church is no longer the centre of community as it was when she was a child (Dawson, 2022, 27:45). Her lifetime church closed 5 years, its organ sadly lost with it.

What once was a cultural soundmark (Truax, 1999) of utmost importance in a Christian, church-centric culture has now become a disappearing sound as we shift into a more secular society. Resulting attempts to preserve this instrument have led to a wide range of recontextualizations. Contemporary composer and organist, Claire M Singer has been musical director of the Union Chapel organ since 2012. The Union Chapel, while still occasionally holding services, is best known as a venue which hosts events all the way from comedy to experimental music. Since 2016, Singer has curated the festival Organ Reframed. The festival provides a space for experimental musicians to bring the organ into the 21st century, and composers are commissioned to write new music for the organ that ‘challenge preconceptions’ into order to draw new audiences (Union Chapel, 2022). Singer’s own work focuses on the timbral potential of the organ stops, a prime example is her piece Solas (Singer, 2016). Lee Scott Newcombe’s instrument, the Anemoi, also vastly reimagines the organ (figure 2). Newcombe separates 54 metal flue pipes into 6 groupings (or manuals), which can then be played by individually blowing on each pipe. Newcombe then carefully changes the pitch of these pipes to create a strong beating effect (Newcombe, 2022).

The organ has also been recontextualised in less experimental ways (although still radically creative) as seen in sell out event, Organoke. The yearly event, held in St Gile’s Camberwell, sees modern pop classics played on the oldest church organ in London for a group sing-along (Organoke, 2023). In a society feeling the loss of a sense of community that once came from church (DeBotton, Chapter 2), Organoke enables people to have secular fun around a traditionally non-secular instrument. This popular event in turn raises funds for the upkeep of the organ (Organoke, 2023). This event, along with Organ Reframed, demonstrates that when the organ is separated from its religious context, the public show interest and are brought together in new ways.

The Henry Jones Organ was installed in London Bridge station on 30th July 2022. It was installed by the charity Pipe Up with the intention that it be playable by members of the public (Pipe Up, 2022). Indeed, it is very accessible and I have greatly enjoyed listening to the changing soundscape on my walk from the trains to the tube. It is like an organ lucky dip, will there be a fugue today, or manic cluster chord from an excited child? All of it delights me. The sound of this organ represents curiosity, creativity and intentional noise making. This is made particularly stark against the backdrop of the noisy ‘complex sound system’ (Augoyard and Torgue, 2006, p. 12) that is London Bridge train station. In fact, the sound of the organ would not mean these things to me if it was not in a train station. Barry Truax uses the visual analogy of the relationship between figure and ground in a picture to emphasize the importance of a sound signal’s context (1999); it is the ambient context that gives the sound signal meaning. Where the sound of the station is directly produced by a crowd in transit, the sound of the organ represents the individual taking to time to stop and, more often than not, discover something new.

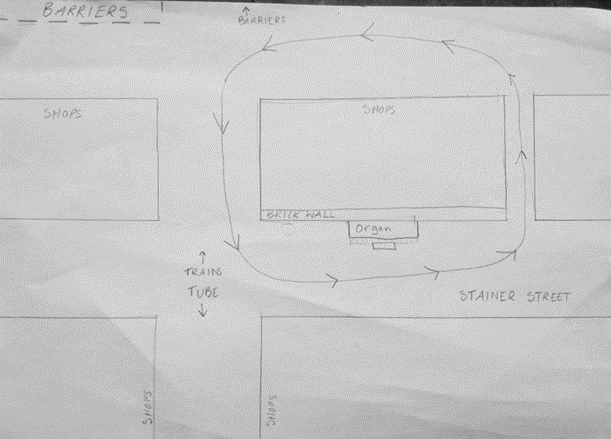

The juxtaposition of these contrasting sonic situations fascinates me. In London Bridge Station and Organ, 08/01/23 I capture this tension in real time, by constructing a circular soundwalk that repeatedly shifts the foreground of the soundscape between station ambience and organ. Whilst the definition of soundwalking remains vague (or rather, open ended), it is a practise that focuses primarily on ‘listening to the environment’ (Westerkamp, 1974). This intense concentration on audible surroundings can then be used for performance art, compositional or recording purposes, or remain as a real time sonic experience (Drever, 2009, p. 163). As someone who has a great deal of trouble filtering out sound, I often feel I have no choice but to soundwalk. The soundwalk I constructed my piece around is short and repetitive (taking approx. 45seconds per rotation), allowing me space and time for processing my surroundings as well as witnessing their change over time (figure 3).

It also incorporates 4 different types of passage ways, from the wide space where the barriers are to the narrow passage after the organ, taking the participant through a changeable sonic and visual journey. There is a point behind the brick wall where the organ disappears completely and the ambience of the train station comes to the forefront; a real time juxtaposition of the two soundscapes. This soundwalk encapsulates the moment in my journey where the organ appears and is gone, and allows this emergence to be repeated over and over. On the day I recorded, I circled the organ for upwards of two hours, capturing a diverse range of organ explorations. I stitched these recordings together, to demonstrate the variety of expressions (pop, classical, improvised and children having fun). I also took out some of the low end to reduce rumbling for a cleaner recording (figure 4). Other than this, there was no editing as most of the contrast was captured in the recording itself.

Figure 4: My Reaper project showing stitched together audio files and EQ

To contextualise the piece, I included a recording of the walk from the train to the organ at the start and from the organ to the tube at the end. This frames the piece with the monotony of commuting and presents the organ as unexpected, with just enough time for the organ to feel out of nowhere at the start, and for the organ to fade from memory at the end. By placing an organ, with all its non-secular connotations, in an ordinary, transient place, a vast array new opportunities open up. First, and perhaps most obvious, is the chance for people to play an organ- an instrument that is, inaccessible to most. People who are not from a wealthy or Christian upbringing are afforded the ability to continue the life of a disappearing sound. Second, is the possibility to shift a traveller’s mentality from that of transience to in-the-moment discovery, whether that is the person playing, or the people listening as they walk by. Finally, the Henry Jones organ provides a new meeting point for strangers; something so remarkable and unexpected that people can bond over excitement, confusion or even shared songs (as heard towards the end of the piece). For me, it represents a much needed moment of humanity in an overwhelming commute, and my piece is an ode to that respite.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Augé Marc (2008) Non-places: Introduction to supermodernity. London: Verso.

Augoyard, J, & Torgue, H 2006, Sonic Experience : A Guide to Everyday Sounds, McGill- Queen's University Press, Montreal. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [18 January 2023].

Botton, A.D. (2013) Religion for atheists: A non-believer's guide to the uses of religion. New York: Vintage International.

Union Chapel. (2022) Organ Reframed, Organ Reframed | Union Chapel. Available at: https://unionchapel.org.uk/venue/organ-reframed (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Singer, C. M. (2016) Solas, Bandcamp. Available at:

LaBelle, B. (2010) Acoustic territories: Sound culture and everyday life. New York: Bloomsbury Academic & Professional.

Newcombe, L.S. (2022) The Anemoi, LSN. Available at: https://www.leescottnewcombe.com/copy-of-the-diapason (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Dawson, J. (2022), “Organ Stops: Saving the King of Instruments”, 21:10 24/12/2022, BBC4, 60 mins.

Organoke (2023) ORGANOKE. Available at: https://www.organoke.com/ (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Pipe up for Pipe Organs: Heritage charity fighting to save the King of Instruments (2022) Pipe Up. Available at: https://www.pipe-up.org.uk/ (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

RIBA (no date) London Bridge Station, RIBA. Available at: https://www.architecture.com/awards-and-competitions-landing-page/awards/riba-regional-awards/riba-london-award-winners/2019/london-bridge-station (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Drever, J.L. (2009) “Soundwalking: Aural Excursions into the Everyda,” in The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music. Ed. Saunders, J. Farnham, England: Ashgate.

Taylor Guitars (no date) Western Red Cedar, Taylor Guitars. Available at: https://www.taylorguitars.com/guitars/acoustic/features/woods/top-woods/western-red-cedar (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Truax, B. (1999) HANDBOOK FOR ACOUSTIC ECOLOGY, Handbook Index. Available at: http://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studio-webdav/handbook/index.html (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Westerkamp, H. ‘Soundwalking’, Sound Heritage, Vol. III No. 4 (1974).

Wilson, R. (2021) Building study: London bridge station redevelopment, The Architects' Journal. Available at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/buildings/building-study-london-bridge-station-redevelopment (Accessed: January 18, 2023).